Sourdough Starters: An Origin Story

Image courtesy of http://www.historicalcookingproject.com/2014/12/guest-post-ancient-egyptian-bread-by.html

Sourdough breads are my favorites because there’s no other method for baking that gives you such complex, deep flavor, nor for making breads with as much nutritional density; health benefit; or real, proper fermentation. Bread made from commercial yeast is risen by the farts of yeast alone rather than through real fermentation. Yes, that’s right - I said farts. Most people will tell you yeast rises bread “as a byproduct of yeast development” or similar, but that’s just a fancy way of saying that the yeast are farting enough to fill your dough up with carbon dioxide. They also pee out alcohol into your dough as they’re eating the sugar in your dough’s grain, but that all cooks off when you bake the loaf. True story: you just can’t make this stuff up.

Image courtesy of https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/02/28/588969884/the-rise-of-yeast-how-civilization-was-shaped-by-sugar-fungi

The history of sourdough is a bit murky, but this has been the primary method of baking leavened bread until 1857. Before then, the only other way to make risen loaves was to get barm, also called “emptins” in America during the 18th and 19th centuries, from a brewer to use in place of sourdough starter. Barm use popularized around the 15th-century, with the rise of larger brew houses in Europe, but has never gotten the same traffic as sourdough because barm has never been as accessible as the microbes already present in your home and on your grain. Because I brew pre-modern ales with sourdough starter if I don’t want to use yeast saved from a prior batch, I often will use the emptins from those brews to bake bread, thereby giving me two uses for the same portion of starter. These are fun, because the sourdough yeast tends to become much more vigorous after it’s brewed some ale, making for loaves nearly as tall as those you can produce with commercial yeast.

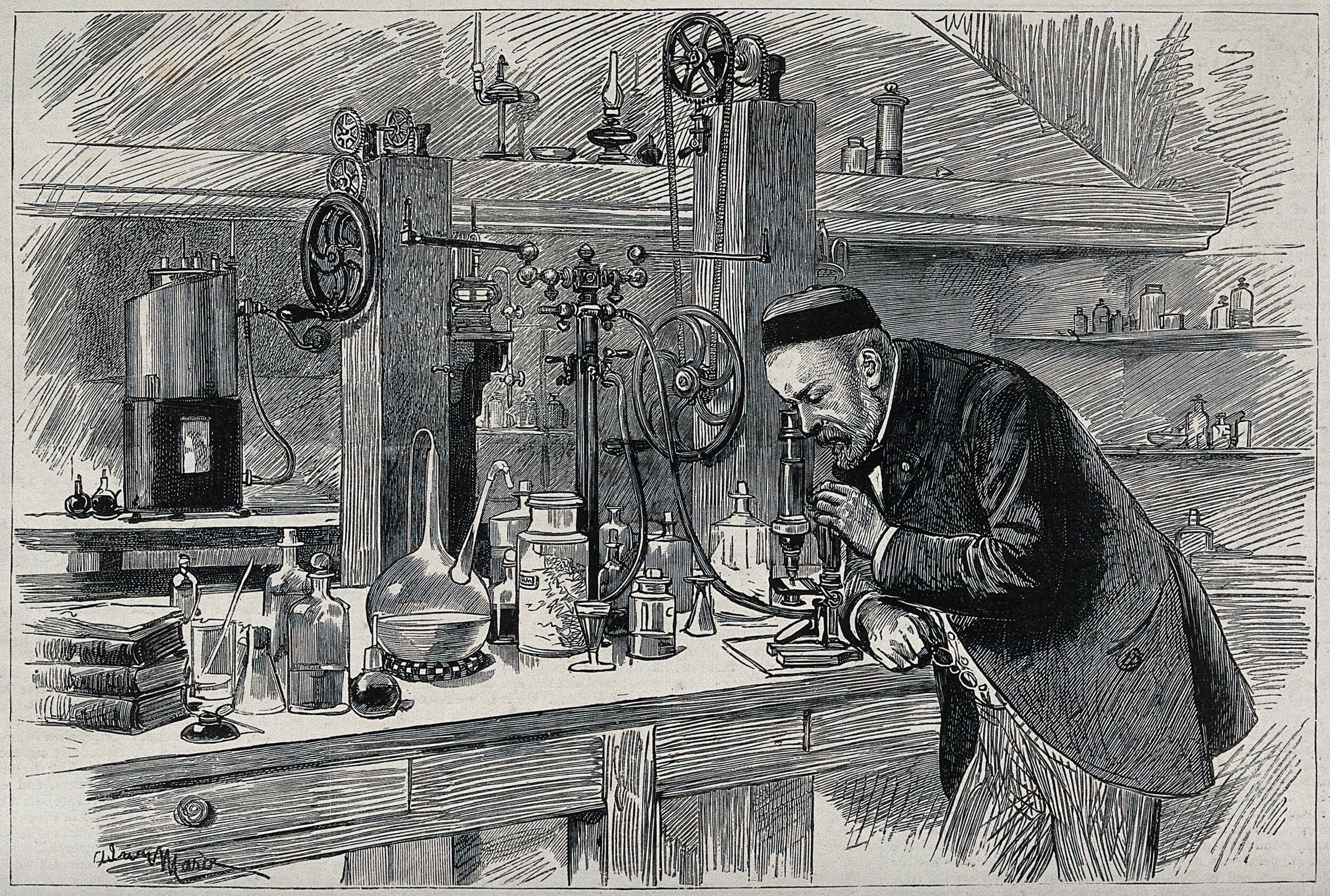

In 1857, Louis Pasteur saw yeast with his microscope. Yeast were then isolated from the bacteria still present in sourdough starters and used to develop commercial yeasts similar to what you can purchase at the grocery store today. With that, bread generally stopped being fermented, and many people make the claim I agree with that bread became a lot less nutritious, and more likely to be involved in bread-related intolerances, than it ever had been in the prior thousands of years.

Image courtesy of https://wellcomecollection.org/works/dpa3xkqp

Although the oldest extant example of bread we have is an unleavened Swiss loaf dated to around 5700 years ago, the oldest evidence of sourdough we currently have hails from Egypt in around 1500BCE, where it is assumed that someone left either a flatbread dough mixture or porridge out overnight. Upon returning, they discovered this mixture was bubbly and smelled differently due to the yeast and bacteria that had colonized it during the maker’s slumber, and for some reason they still baked it. I’m glad they did, but I can’t imagine I would have been such an intrepid bread explorer unless I really didn’t have any food to spare. I assume whomever this glorious person was couldn’t afford to waste the grain. Either way, although the Egyptians didn’t record the original maker(s) of sourdough starter, they certainly used a portion of their prolific writing habits to talk a lot about bread.

Image courtesy of https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/X1-(letter_T)_bread_bun_-_feminine_(Egyptian_t_hieroglyph)#/media/File:Flickr_-_schmuela_-_IMG_7153.jpg

There are a lot of theories about this process, and whether this occurred due to the Egyptian love of brewing (beer was big back then, y’all) or if it was a spontaneous occurrence in the more traditional sense, but either way the practice spread all over the known world, and with a quickness. Risen loaves are more filling despite being primarily comprised of air, and they are definitely more nutritious than unleavened due to the fermentation process, so by fermenting your bread you could feed more people, and better, than you otherwise could with the same amount of starting grain. This is big, because pre-Industrial farming, producing massive surpluses of grain just wasn’t really a thing. Beyond the awesome of better bread, though, people were able to feed their pet starter and travel with it, allowing bread to rise in transit, which assisted in the colonization of the United States and other spaces around the world. In the American West, some people even used their precious starters to tan hides for both personal use and sale, because the acidity of the starters helped soften pelts with a bit less work than many other methods.

Image courtesy of http://www.armitchellmuseum.com/store/p83/Gold_Panner.html

This piece is for sale, in case anyone wants to send me a present.

After the advent of not only commercial yeast but chemical leavening, and large corporate bakeries (think Wonder Bread here), bakers, and particularly home bakers, by and large stopped using sourdough. It still existed, of course, and you can still get starters dating back to at least 1849, but by-and-large, people stopped keeping their sourdough pets.

Image courtesy of https://www.artisanpassion.com/wild-yeast-vs-commercial-yeast/

Blessedly, there is now a resurgence of interest in sourdough baking, which has caused it to become more ubiquitous in stores and bakeries. There’s even a sourdough starter library (I want to go to there), and in Sweden there are sourdough hotels (equivalent to doggie daycare). So interesting has sourdough become, scientists have isolated starter residue from ancient Egyptian pots and revived it, using it to make as close to a traditional ancient Egyptian loaf as it possible. More importantly than even that, though, sourdough has also increased in appeal to home bakers like us, which allows people to reconnect with our historical human roots while empowering us to take control of the flavors and healthfulness of the staple of life, bread.