Viili: An Origin Story

It’s always a good time when you’re talking viili! This culture tends to be a pretty polarizing one: you either love it, or you’re disgusted by it. This is because of the slime factor! Viili is super, super popular in Finland, where most sources claim it comes from (every now and again, Sweden get the credit, and that credit is probably earned), but in America, it’s mostly kids who seem to favor it.

Why, you ask? Because it’s a food you can eat with your hands. True story - I’ve seen it in person! For children, this fits within the category of “toy yogurts” due to its long ropes and slimy texture. My own kid, when she’s eating yogurt (currently she says she’s “tired” of yogurts), considers this to be a favorite, and she likes to show it to her friends. We say that fermenting brings people together, but kids have this down - they pick out the weirdest, coolest culture they can and are like, “yo! Check this stuff out! It will stream like string cheese off your hand and you can lick it up while it drops onto the carpet!” Yeah. Carpet. In theory they’d let it stream back into their bowls, but carpet it is. I really need to stop letting her eat in the living room if I’d like to keep that carpet.

This is also, carpet aside, why adults who didn’t grow up with viili tend to find it off-putting despite the excellence of its flavor. Don’t fret, though! If you’re an adult, you too can not only get used to the texture, but come to enjoy it. Especially if you eat it at work where others can observe! Then it’s basically a prank and a snack in one, and it’s hard to go wrong with that!

Viili is all about the ropes and slime!

As we discussed in the piimä origin story, viili may originally have been the “cream layer” of piimä! So it may have been that our beautiful sundew or butterworts originally are responsible for viili, as they definitely are with piimä.

So why is it so ropey, anyway? Basically because it contains a substance called viilian, which is a polysaccharide produced by a fun-loving bacterium called Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris. Specifically, this is a heteropolysaccharide, which means it has different kinds of molecules instead of just one to make up the compound. Here’s what that can look like:

This is what heteropolysaccharides can look like.

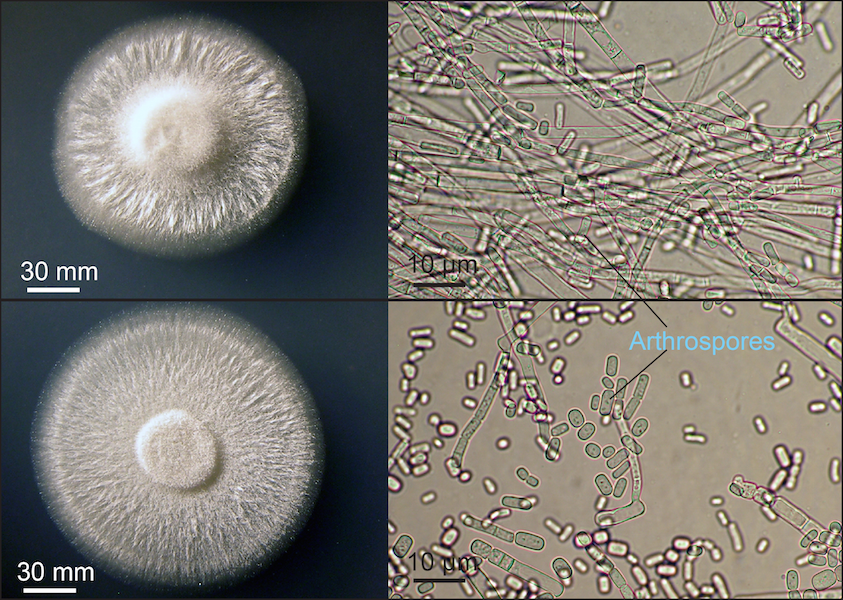

In literally every instance in which you can eat long viili, Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris is in the mix. Short viili? Not so much. Here’s what this little guy looks like:

He’s pretty cute, huh?

So what are the types of viili, exactly?

Long viili: this is the classic, ropey, slimy toy yogurt most people who eat it are talking about.

Long viili with mold: this is not only a thing, it’s basically the highest form of viili you can get. It’s rabidly sought after by viili afficionados. More on this in a bit.

Short viili: short viili comes in two forms - the one you intended to culture, and the one you didn’t. More on this in a bit as well.

This is what moldy viili looks like when it’s cultured. You eat the mold too, which is sweet and creamy.

If the mold-free viili is the “regular” long viili, what’s up with the mold?

We get this question a lot, because why would you want to eat moldy yogurt? Basically for the same reason you eat some cheeses with mold on or in them - it tastes good.

Moldy viili happens when your culture contains the (in my experience) very fickle Geotrichum candidum. This is the same kind of yeast that produces the rinds on brei, camembert, and some chevres. If you eat those cheeses, you know what it’s like already: kind of sweet, creamy in texture, and all around tasty. Although I personally don’t care for the texture of viili (I have trouble with a number of dairy textures, so no surprise here), I think the mold layer is absolutely delicious and yes in all the ways.

The first time I tried it, I had received a tiny portion of “moldy viili” from a fermenting buddy. He spent a loooooooong time trying to find it, because he cared more than I did. Good man, that one. I made it, felt simultaneously intrigued and grossed out, and lifted a tiny, pea-sized bit of the mold out from my spoon. Once I tasted it, I knew why the mold’s appearance was so familiar to me - I am a big cheese eater! My kid said the mold tasted good but got in the way of her fun.

Luckily for her, G. candidum is fickle. Fickle here means, “can get lost with exactly no effort on your part.” Sabrina has had the same issue with it, where you’ve got your batches going and they’re beautifully moldy, and then one day they’re… not anymore. This is also why commercial producers of this type of viili actually add the yeast in themselves - it seems to be the only way to ensure that you can get the mold each time.

A quick health note: if you are immunocompromised, you ought not eat the moldy viili. Although it’s exceedingly rare (100 cases between 1842-2006), G. candidum can cause infection. This mainly means you should have a conversation with your doc before adding it to your diet, but the likelihood is that once your doctor has reviewed all relevant literature, you’re likely good to go!

You didn’t think I’d leave out the picture of our hero of the moldy viili, did you?

Which makes short viili what, exactly? It’s viili without either G. candidum OR Lc. lactis subsp. cremoris. No mold, no ropes. Just viili without the weird. That’s all it is.

There are two ways I’ve found to produce this:

Buy a short viili culture and culture it (simplest), or

Over-ferment your long viili.

That’s it. I couldn’t find any data on how short viili came to be, so my assumption is that it started out over-fermented. The two microbes seem to strongly dislike being over-fermented, because if you do it? Poof they’re gone! I’ve tried this with both moldy and regular ropey viilis, and that event consistently transforms them into short.

Texturally, short viili is mostly like regular yogurt, except it tends a bit more toward lumpiness. You can stir it to fix that right up.

If this is not the texture you’re looking for, go short viili.

What do we like to use it for? Kid, as previously mentioned, prefers to eat it as is (whether the long or short). If I add honey or anything else, she gets upset and says I “ruined” her yogurt. Okay, kid. Sorry ‘bout that.

Me personally? I like to use it in other things. My preferred use is to put extremely over-fermented viili into mashed potatoes, and particularly colcannon (recipe coming on Wednesday!). I also use it in baked goods, in place of sour cream to top soups, added to “cream sauces” in place of the cream (pro-tip: add it at the end of the sauce-making, because it’s already really thick and you can keep the probiotics that way), or in baking. I basically use it the same as I use most other dairy cultures, because outside its texture, it’s a differently flavored version of any other mesophil.

Some really cool information on traditional preparation methods and its popularity in Finland.