Pepper: an Origin Story, Chapter 4

Anas/Getty

Yeah, that’s right. I said chapter. Because at this point, it’s effectively that. Just really short chapters!

We’re backing up a little bit and returning to the end of the War of the Roses. There’s been a lot of conflict over who gets to be in charge over in England, and it really wasn’t pretty. As we all know, There Can Only Be One.

If you didn’t know that, turns out that YouTube has the full movie up there so you can find out!

In the end, it’s Henry VII who takes it, and with that the House of Tudor is established.

The last English monarch to land his spot on the battlefield instead of exclusively via genetics, Henry VII was no slouch. He levies taxes to deal with war debts, marries from the York family to ensure familial ties to help quell rebellions, brutalizes his people, seeks more pepper, and all the stuff you generally expect from these guys. It’s also during Henry VII’s reign that the tremendous paranoia the entire Tudor line is so well known for gets started. Basically anyone with blood ties was suspected of trying to get at the throne, and that led to a lot of weird legal action being taken to hamstring any possible efforts to undermine the crown. Sometimes also led to death.

Lastly, despite a total absence of experience in estate management, Henry was able to rectify England’s economic troubles. He did this in two ways, the first being ruthless with taxation, fines, and protectionist policies. The second, and more relevant way, was that he boned up on trade.

It’s this Henry who recognizes the need to dramatically increase naval power, so although he invests heavily in wool trade and alum from the Ottomans, he also continues buying spice during this time. His primary focus is utilizing England’s rich wool production to better his access to other stuff, rather than taking over the spice trade at this point.

You really needed to have your pepper on point, also, if he was coming to visit.

“Priory register detailing the food ordered for a visit by King Henry VII in around 1501.It includes the following: 3 and a half tuns of ale (a 'tun' of liquid was around 240-250 gallons),1 tun of wine,4 pounds of pepper,1 pound of saffron,1 pound of cloves and mace,2 pounds of cinnamon,2 pounds of ginger,12 pounds of small raisins,8 pounds of dates,20 pounds of sugar,4 oxen,20 sheep,3 dozen capons,3 dozen chickens,2 larded capons for the King,4 cygnets,2 peacocks,18 rabbits,100 eggs.”

Despite his heavier focus on wool, Henry really didn’t forget that he needed a direct route to pepper in India. In fact, like Isabella with Columbus, he sponsored John Cabot’s several journeys to India, which in this case also happened to be North America instead. Cabot was the first European to set foot on American soil this far north since the earlier Scandinavian exploration of Vinland we talked about in one of the prior parts. They’re all running together in my mind, so I don’t remember which. No one is sure where Cabot landed, but it was somewhere between Maine and Labrador.

Cabot and his crew disappear during his last journey, and there are lots of theories about what happened. After sponsoring these voyages, Henry also sponsors voyages from Cabot’s sons and other supporters, ultimately resulting in William Weston leading the first English exploration of North America in either 1499 or 1500. No one is sure exactly which year.

Henry VII is probably why we all know the Welsh Dragon. Although the symbol is from a much earlier time period, it became the official symbol of Wales under him. This was to symbolize the critical aid that Henry received from the Welsh in securing the throne. Henry VII was also of Welsh ancestry, and the Tudor name stems from that heritage.

I’m Henry VIII, I am

Henry VIII y’all already know the basics for. He killed a bunch of wives, was really quite out of his mind, sponsored and acted in Robin Hood plays, broke from Rome, all the usual. Ross seemed displeased that I wasn’t willing to tell y’all all about how amazing this Henry was with regard to military stuff in his pre-injuries and tertiary syphilis days, but if I decided to do that, I may as well just hand my laptop over and tell him to write his own article!

So just know, that if you’re into that sort of thing, there’s a wealth of research you can do on Henry VIII and his various militaristic prowesses (and lack thereof). Ross is still talking about archers as I write. Later on, Henry starts to stink at military stuff, which is what people usually talk about. I noticed that Ross so neatly dodges that segment that I wouldn’t have known stuff was missing from his narrative if I hadn’t already known stuff was missing from his narrative. I was impressed.

After Henry fell off a horse when he was whacked with some sort of stick-ish weapon that I forgot during a game, it’s believed he did have brain damage from the fall. Contemporaneous reports state that he was unconscious for around 2 hours after the fall and that he did exhibit personality changes afterward. Basically, a sports injury is what happened to Henry, and then the increased madness from tertiary syphilis and the 6-week mercury treatment they used to treat syphilis back in the day.

Of principle note regarding Henry VIII and pepper, his primary deal was that he liked it a lot. Henry drained the royal coffers his dad had restored by throwing parties that cost millions upon millions of current day dollars, and once they were drained he needed a new way to get money for it. His solution, once he’d needed a divorce so badly he created his own religion to make it happen (Church of England), was to raid the Catholic monasteries all Viking style, swoop up all the loot, and use it for more parties.

Dude loved his parties. Every time I read Henry VIII history, I feel like I’m reading about what would happen to college fraternities if their members never graduated and just kept on keepin’ on.

I’ve been asked twice while writing this article if Henry was as portly before all the bad bodily things befell him as we all commonly know him to have been in his later years. I’m including this because some of y’all might also have wondered; the answer is no. He was still a playboy, he was still a jokester, he was still a partier and a lover of food, but no. His injuries and illnesses, later compounded by the obesity itself, dramatically limited the amount of exercise he could get while living in a time when excessive feasting was the norm for the upper class.

Now Ross is talking about all the fortresses gained from destroying monasteries. I’m just here for the parties and pepper, not for the fortresses!

This pepper mill belonged to Henry VIII and was found on the sunken Mary Rose, his favorite ship. “When archaeologists opened this pepper mill from the Mary Rose they were met with a whiff of the spice and found peppercorns still inside.Being able to put pepper on your food in Tudor period was a sign of wealth as it was an expensive luxury.”

Last thing for Henry VIII is this song, which I expect y’all know already. I’m putting it here so I can get it out of my head. Y’all probably knew this was coming, though, based on section title for this Henry.

Elizabeth I

There are other monarchs between Henry VIII and his legally (but not actually) illegitimate daughter Elizabeth I, but we’re not going to worry about that right now since it’s interesting but not hugely relevant to pepper. Elizabeth is the last Tudor before the ascension of the Stuarts, the Scottish arm of the family.

Elizabeth is also who is really most important regarding pepper, because she builds upon the work of her grandfather in a dramatic and globally-changing manner. Like Ælfred and Æthelstan realizing their family dream of a united England. I’m going to skip over the majority of the details I personally find most interesting about Elizabeth, because I really would like to get us through to around 1750 today. And because not super relevant to pepper.

One thing I do want to say about her, though, is that she and I share a love of one specific dye: woad. She loved woad like the dickens, which makes sense since it produces such a lovely range of blue colors. It smells really bad when being used, though, so she kept her massive woad fields and processing “centers” (they weren’t really centers) far away outside the walls so she wouldn’t have to smell the nastiness of the favored dye.

Clearly she was keeping up with the equally important wool and textiles industry, too.

This is woad at the stage where it needs to be used for dyeing. Once it’s in its second year and produces those lovely yellow flowers you can’t see here, it’s useless as a dye. I have woad seeds, and hope to one day plant them at my kid’s school, where I intend to amend the community garden we’re developing to include a dyer’s garden. This is also the plant that Picts and a few other Celtic tribes in the British Isles used to paint themselves with before war so they’d look all scary. Y’all would recognize this from Braveheart, even though the Scots didn’t actually perform this pre-war step. There’s also zip for evidence that Scots were using tartans yet, and instead they dressed pretty much the same as everyone else in Europe during that era. Just sayin’.

These are some of the blues you can get from woad. The final product’s color and saturation will depend on what mordant, if any, was used in the dyeing process. Mordants are chemical additives that help set the color so they’re actually dyed instead of stained (stains come out; dyes do not). This really is rather a lot of article space dedicated to a dyer’s plant that has exactly nothing to do with pepper. Let’s move on from this before I get trapped in a thought loop.

Pepper is a big deal for Elizabeth because it not only creates a situation where England can develop naval and economic supremacy over Portugal, she can fight against Dutch takeovers of the spice trade. They do a lot of warring, the Dutch and the English, all in the name of spices. Really, everyone does a lot of warring, but I’m excluding the more “minor” nations in the events. It’s hard for me to use the word “minor” because I’m aware of how not minor these events were for the colonial subjects of the “minor” nations, and how not minor they are in any holistic examination of Europe’s history during this period.

People still don’t know a ton about pepper at this point, botanically or otherwise, and you can see some of that learning process below.

This is a very cool text, done by Walter Bailey in 1588 (30 years into Elizabeth’s reign). For those of you who can’t read this, here’s what it says in more modern English (with spellings mostly normalized and some words entirely modernized):

Thus as Dioscorides writes, and hereby also we are to understand that the old saying is fabulous and untrue, that pepper is made black with fire. For the merchants which brought the peppers, said, that serpents and venomous beasts did use much to be under these pepper trees, and that they were driven to stay away those serpents with making fires under the trees, before they durst gather the peppers, and so the pepper was made black by the fire.

But now we learn by the histories penned by the latter writers, that all this is untrue, and that black pepper is of that color by his own kind, when it is ripe: and so that for white pepper is of his own kind, even of that color when it is ripe. As the red grape has that color naturally when it is ripe, and the white grape keeps his color even to his full ripeness. Wherefore those writers were much deceived, which affirmed, that white and black pepper were of one tree: and that white pepper was the fruit not thoroughly ripe, and that black pepper was the same perfectly ripe. For (say they) as in our country, when we gather apples, all of the same tree are not of like ripeness, some not full ripe, some full ripe, some over ripe, and all are gathered at one time: so, say these men, when the merchants do gather pepper, some grains are thoroughly ripe, and they black and wrinkled, some not full ripe, and they whiter in color, and smooth not wrinkled. But it appears that by which they have delivered to us, which have seen and gathered both these kinds of peppers, that they are gathered of several trees, and that each does perfectly ripe in his kind, and each retains his color: the white grain when it is ripe keeps the white color, and the black pepper when it is ripe keeps his black color. Even as the white grape being ripe remains white, and the red grape red, and yet each do come off several vine trees different in kind.

Because “[h]er mind has no womanly weakness,her perseverance is equal to that of a man, and her memory long keeps what it quickly picks up[,]” Elizabeth was given the rigorous education normally reserved for men at her time (Roger Ascham). This might not seem like a big deal to us, because woman are all about education these days, but it was a big deal to them. Education is power, and you ordinarily don’t want to let the fairer sex have either of those. Either way, Ascham wrote a lot about the incredible intellect of Elizabeth.

She continued along with exploring North America, per her grandfather’s mission, in an attempt to make it to India to control spices. This is a thing that happened that had far more to do with the formation of the States and Canada than you might expect.

Also important to note along the gender lines is that this crazy power that Elizabeth had came with two options: incredible devotion by some, unending scrutiny by others. To be honest, this didn’t look a whole lot different from current American political debates about President Trump, though the subject matter of those debates was definitely different.

These debates were because England didn’t really do female rulers. At least not for a long time. Seriously; the most recent, kind-of example before Elizabeth’s sisters of a woman with the type of reputation and power we’re seeing in Elizabeth is Æthelfled, King Ælfred’s daughter who was not a queen but rather a lady; she was nearly 800 years prior to Elizabeth.

We did have the disputed Empress Matilda in 1114, though. Prior to that? Cenwahl’s wife Queen Seaxburh helped him rule from 672 to 674. She was apparently really mean and controlling, so thereafter Saxons simply didn’t allow queens. As you can understand, this was a lot for them to come to grips with.

After Henry’s death, Lady Jane Grey made it 9 days, and Bloody Mary a bit over 5 years. After Mary was Phillip (just over 4), then onto Elizabeth.

Because Elizabeth’s predecessors didn’t do as good a job of ruling as people would’ve liked, and because she was a she, the scrutiny on Elizabeth was intense. She was an incredibly formidable woman, and had to entirely redesign the ways in which a woman should rule so she wouldn’t have the same troubles as her recent predecessors.

Pertaining to Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen, it is believed that she remained unmarried, however many potential suitors she entertained for appearances, to maintain sole power over the nation. By refusing a husband, she basically takes England as her mate and its subjects become her children. In effect, she becomes like Daenerys from Game of Thrones. By eschewing marriage, however, she left no heir to continue her line after her reign. This becomes a problem because it hands the monarchy over to the Scots. For some reason I will never understand, due to my great affection for the Scots, no one wanted them in charge!

You really can’t always get what you want, so the Scots do take the throne once Elizabeth dies. Remaining free of a life-mate was part of her Woman Power redesign of how one should rule, as marriage would have stripped her of her power and subjugated her to whomever she married. I feel this was a worthy trade-off, personally. She also explains her position on the matter in 1601, when she states in The Golden Speech,

I do assure you, there is no prince that loveth his subjects better, or whose love can countervail our love. There is no jewel, be it of never so rich a price, which I set before this jewel; I mean, your love: for I do more esteem of it, than of any treasure or riches.

This is the full Golden Speech (1601), which I translate as follows:

Her Majesty’s most princely answer, delivered by herself at the Court of Whitehall, on the last day of November 1601: When the Speaker of the Lower House of Parliament (assisted with the greatest part of the Knights and Burgesses) had presented their humble thanks for her free and gracious favor in preventing and reforming of sundry grievances, by abuse of many Grants, commonly called Monopolies. The same being taken verbatim in writing by A.B. as near as could possible set it down. Imprinted at London. Anno 1601. (title page)

[skipping the repeat of title page on page 138] Mr. Speaker, we perceive by you, whom we did constitute the mouth of our Lower House, how with even consent they are fallen into the due consideration of the (138)

precious gift of thankfulness, most usually least esteemed, where it is best deserved. And therefore we charge you tell them how acceptable such sacrifice is worthily of a loving King, who doubts much whether the given thanks can be of more poise than the owed is to them: and suppose that they had done more for us, than they themselves believe. And this is our reason: Who keeps their Sovereign from the lapse of error, in which, by ignorance, and not by intent, they might have fallen; what thanks they deserve, we know, though you may guess. And as nothing is more dear to us than the loving conservation of our subjects’ hearts, What an underserved doubt we might have incurred, if the abusers of our liberality, the thrallers of our people (2)

the wringers of the poor had not been told [to] us! Which, ere our heart or hand agree unto, which we had neither: and do thank you more, supposing that such griefs touch not upon you in particular [emphasis mine]. We trust there resides, in their conceits of us, no such simple cares of their good, whom we so dearly prize, that our hand should passe, outght that might injury any, though they doubt not it is lawful for our kingly state to grant gifts of sundry sorts of who we make election, either for service done, or to merit to be deserved, as being for a King to make choice on who to bestor benefits, more to one then another. You must not beguile yourselves, nor wrong us, to think that the glowing luster of a glittering glory of a King’s title may so extol us, that we think all (3)

is lawful what we list, not caring what we do: Lord, how far should you be off from our conceits! For our part, we vow unto you, that we suppose Physicians aromatic favors, which in the top of the Potion they deceive the Patients with, or Gilded drugs that they cover their bittersweet with, are not more beguilers of senses than the vain board of a kingly name may deceive the ignorant of such an office. I grant, that such a Prince, as cares not for the dnitity, nor passes not how the reins should be guided, so be rule, to such a one, it may seem an easy business. But you are cumbered (I dare assume) with no such Princh, but such a one, as looks how to give account before another Tribunal seat than this world affords, and that hopes, what if we (4)

discharge with conscience what he bids, will not lay to our charge the fault that our Substitutes (not being our crime) fall in. We think ourselves most fortunately born under such a star, as we have been enabled by God’s power to have saved you under our reign, from foreign foes, from Tyrants’ rule, and from your own ruin; and do confess, that we pass, not so much to be a Queen, as to be a Queen of such subjects, for whom (God is witness, without boast or want) we would willing lose our life, ere see such to perish. I bless God, he has never given me this fault of fear; for he knows best; whether ever fear possessed me, for all my dangers: I know it is his gift; and not to hide his glory, I say it. For were it not for conscience, and for (5)

your sake, I would willingly yield another to my place, so great is my pride in reigning, that she that wishes no longer to be, then Best and Most would have me so. You know our preference cannot assist each action, but must distribute in sundry sorts to divers kinds our commands. If they (as the greatest numbers be commonly the worst) should (as I doubt not that some do) abuse their charge, annoy whom they should help, and dishonor their king, whom they should serve: yet we verily believe, that all you will (in your best judgment) discharge us from such guilts. Thus we commend us to your constant faith, and yourselves to your best fortunes (6).

You can see that these peeps were still giving her a lot of trouble, to the point that she has to refer to herself in the masculine abstract. This was, for reference, 2 years before her death and one year after she granted the East India Company charter. For reference, she ruled for a whopping 44 years (plus a bit), so she’d been dealing with attitude the whole time.

Before 1600, Elizabeth and her Tudor predecessors primarily were fixated on finding a Northern passage to India. This never really panned, but they do colonize most of the then-known parts of North America that the French didn’t already hold. Also had wars trying to get more of the landmass for themselves. Also a lot of this had as much to do with overpopulation in England as it did with pepper, because for real they needed to get those people off the island and onto somewhere else. America was fantastic for that, as Australia and other places would later become. Also a super easy way to get rid of people of faiths that even the über religiously tolerant Elizabeth wasn’t all that keen on. Her successors hated people like the Puritans more, though, and so they had fled to the Dutch Republic, discovered they might actually become like the Dutch if they stayed, and booked it over to the Americas as they were newly being colonized in order to make a home of their own. This isn’t exactly mirrored in the Mormon journey to Utah, but it really isn’t a stretch to see the pattern here as pertains to British-based peoples and religious intolerance (whether across the pond or right here in North America).

This is the highly recognizable Armada Portrait, which was commissioned after Elizabeth trounced Spain.

We made it!

It’s in her era that Sirs Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh start wandering about, too. Because she paid them to. Drake does, as you’ll see in the picture below, manage routes to India from around Africa and South America, and along the way the found a treasure trove of new sundries that offered extraordinary wealth to Her Majesty and himself. Vanilla, chocolate, potatoes, chiles (which end up becoming popular, after all), maize/corn, peanuts, turkey, new beans, squashes, new nuts, grains of paradise (a pepper-like spice from Western Africa), tomatoes, and all manner of new wares to jazz up the table!

It’s really quite a lot of money spent and earned exploring Atlantic routes to India. Piracy, also, is important here because Elizabeth’s tendency to shrug about the practice is a big part of how they got the Spanish out of a number of areas they were invested in securing.

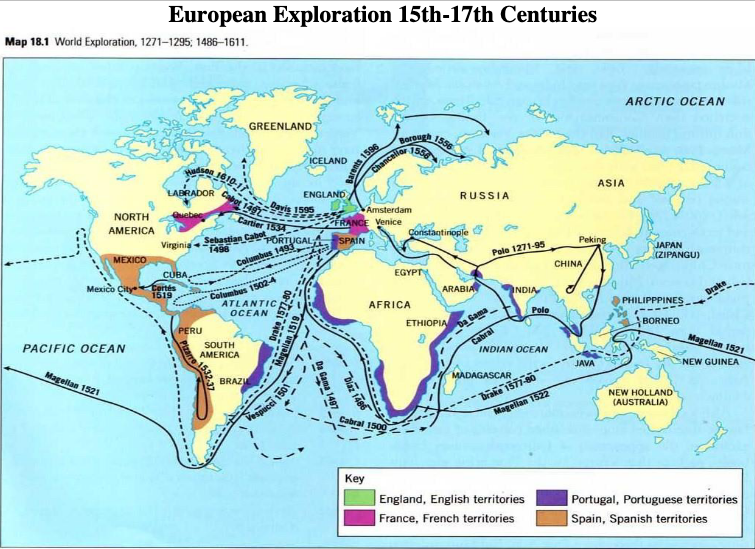

This map shows you what most nations were up to with these routes. The Dutch don’t really need their own during most of this period, since they were mainly working for the Portuguese. You can see that 1577-1580 is the golden period for getting England into this game. I personally find this map most usable if one uses their finger to keep track of where the line one wants is going. Also, the gap in the map dates, I believe, stems from the Crusades.

What happens in India is that although the Portuguese (and Dutch) are primarily invested in the Western coast of India, the English want the mainland. Well, and everything else, but the big push here is to come on over from the east and work their way in. This isn’t actually happening during the years this map represents, but is what happens later.

In the map’s period, it’s all Spice Islands for the English. England get pushed out of the islands by the Dutch by 1623, who at this time were centralized into the Dutch East India Company. From then, it’s mainland India that England is in, and largely relegated to fibres and textiles. Although both companies were called “India” companies but weren’t always operating in India, it’s important to note that during this time that the whole region was called “the East Indies.” Consequently, the name India has a bit of float, geographically, in terms of how we may choose to name our nationalized mercantile businesses.

“This map of the East Indies was originally printed in the late sixteenth century to entice Dutch investors to take control of the region and the spice trade from the Portuguese. Note the spices (nutmeg, cloves, and sandalwood) on the bottom edge.” This is from before the Dutch had arrived as a major player.

The Dutch Republic snags Malacca in 1641, and the Malay islands and others along with it, followed quickly by control of the cinnamon trade in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1658 and a big win in control of the Malabar coast (western India) in 1663. By the end of the 17th-century, the Dutch Republic pretty much owns the East Indies spice trade. And like that, the Dutch had become the new Venetians! They were really not playing about maintaining an iron grip on the spice trade, so they literally burned trees/plants down if the prices of a given spice were falling too low. Can’t buy what doesn’t exist, so yay higher prices! Pepper was a constant shift in which cartel ran the show, huh?

No matter, says the English! Giant subcontinent, so sneaky sneaky let’s go from the other side! Everyone is so sneaky during this part of the history, in the same ways that Child Tester was when she was 2. Where you look at it and you’re like, “really? This is really what you view as sneaky? That’s adorbs!” Because the Dutch really were sneaky as they initially took over the region, but the English were fairly lazy about that and just went around. What they were really doing over there during this time of Dutch supremacy, however, had zip to do with pepper. They were doing silk and cotton from India, which later would segue into the all-important, ever-coveted spices.

As they work silk and cotton, the English press further and further into mainland India, eventually coming to dominate the textiles industry. For most of this period, that’s the sole focus of the British East India Company because they cannot yet find a chink in the Dutch East India Company’s proverbial pepper armor.

I know I said we weren’t going to talk about France, but now we’re going to talk about France. Specifically this guy:

Louis XIV. He was, at one point, the most powerful dude in all of Europe. It is from this Louis that men start wearing wigs again, because he didn’t enjoy the balding process and accordingly sought to cover it up. Enter trickle down fashion! High heels during this time were also worn by men, not women. Originally, heels were created to aid men in war-related horseback riding, but that ultimately was appropriated by Catherine de Medici. She popularized it briefly for women, but then when she died, women stopped wearing them because men preferred to be taller. Women also used to wear shockingly tall platform shoes when they couldn’t wear heels before men decided they needed to be taller.

A couple centuries later, Louis was super into heels. It became a status symbol to wear them, and anyone without permission to do so probably knew they’d be beheaded for the fashion statement well before it happened to them. Beheading did sometimes happen to them, though. Women didn’t wear heels during this time; just men of extraordinary means and status. Women “get” to keep heels later after men give up on them because women liked them so much. It’s a tragedy, really, that women got stuck with these when men could’ve kept them.

Nine Years War (1688-1697)

This war takes place on multiple continents, but we’re going to ignore most of that and focus on the eastern portion that is, alongside the onset of a global reduction in spice demand (in the 1720s), largely responsible for the onset of the Dutch East India Company’s collapse.

The long and short of what happens to lead up to this is that France supports the Dutch through a bunch of wars, which later backfires on them because. In 1668, the Dutch Republic makes a Triple Alliance with England and the Swedish empire to balk against French actions taken in the Spanish Netherlands. France basically got too big for its britches; rebellion ensues. Eventually, Sweden and England bail on the Dutch Republic and back France during the Franco-Dutch War. Does this read like a soap opera to y’all? Because it does to me.

Fueled by frustration over his lack of success in the Franco-Dutch War that preceded this war, Louis is ready to double down on his efforts, albeit with a strategy change. He’s now powerful enough to simply threaten different nations into becoming allies, and this saves him a lot of resources by not having to war with those powers, too.

Tantrums happen. “Tantrums” is a term that here means “people of power get insulted, flip out, and start wars.” He also badly wants to spread Catholicism as the correct faith for Europeans, so there’s that as well. At some point, Charles II (Spain) is over France again and turns against them. What is, in effect, starts as a little world war gets weird fast, with countries switching sides seemingly randomly, a lot of countries hating on France, and ultimately turns into a massive world war. Every continent that had Europeans on it was involved in some capacity. It was crazy pants, for sure.

They are largely fighting over land and God, as is representative of the entire exploratory period. Louis was so antagonistic (what a nice, understatement kind of word!) toward Hugenots that it really did cause him issues with other European powers. Under James II (English monarch 1685-1688), England was once again Catholic, though at this time was also friendly to Protestants. European Protestant nations banded together with England and Spain to lay the smack down on France. Good times!

In 1697, the Swedes function as mediators (though not alone) and negotiate a treaty, called the Peace of Ryswick, between Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance. As happens in all compromises, no one is really happy with the outcome. The political landscape, however is forever changed, and this legitimately does knock the Dutch down a few pegs, setting them up to lose control of their slice of the East Indies pie once they’d spent all their funds on warring and could no longer continue their impressive economic expansion as a result.

In 1720, the spice boom busts. It ain’t pretty, folks. England, being primarily invested in textiles, is largely shielded from the economic effects of this incident.

This tech didn’t exist then, obviously, but this is how “not pretty” it all was.

Ross admonished me for not including the following song in place of this picture, and he’s right so I’m giving both.

The Dutch East India Company folds in 1799. By 1817, the British finally manage to secure some valid nutmeg seeds so they could hit the Dutch spice trade with the death blow while simultaneously affording themselves increased control of the region. The Dutch used to soak nutmeg seeds in lime so they couldn’t germinate, which is why the seed theft mattered. The lime treatment didn’t affect the quality of the spice, but did render it impossible to plant groves elsewhere.

Once the Brits could plant their own nutmeg, they did this in Ceylon and Singapore, thus effectively crushing the vestiges of the Dutch spice trade. We are largely talking about nutmeg in this moment because it can be tough to separate the histories of other Asian spices from the history of pepper. Pepper is why they knew about and sought most of these others so actively, and so the histories are tied in knots that can’t really be fully severed. I will probably never write about another spice from this region again, because anything further I would want to say is already contained in the history of pepper.

We went a lot past 1750, didn’t we? I really wanted to finish up with the Dutch while we were already focusing on them. Next week, I anticipate wrapping up pepper entirely! We’re going to be returning to England next week so we can get caught up there before turning our attention to pepper/spices and the Americas. As we do this, we’ll bring pepper history into modernity so we finally can see how pepper, which currently comprises approximately 20% of the global spice trade, gets relegated to the disposable packets that’re responsible for this series!