Pepper: an Origin Story, Chapter 5 (The End)

We’ve made it to the finish line! This is very exciting. Now, we’re returning to England, which we mostly left off from around 1720! Just 300 years left for today! What’s happened now is that the Dutch cartels have imploded and there’s a massive spice bust. England, largely focused on textiles during Dutch supremacy of the region, is well-insulated from the devastating effects of the bust. Other European powers take a leaf from England’s book and start stealing seeds, colonizing nations with similar climates to India and Indonesia, and growing their own spices for export to Europe!

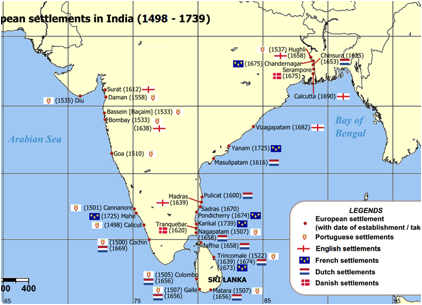

This map gives you a good idea of how things were going during the early this period and also last post’s period.

What the East India Company (EIC) was primarily up to during this period was simply protecting the loot. They didn’t really get involved in local politics and whatnot until 1757, when there was a local uprising in Bengal, funded by the French and led by Siraj ud-Daula. This all results in the Battle of Plassey. From here on out, the EIC began to actively “administer” its territories, levying taxes and all sorts of other unacceptable practices. This battle really is the defining moment in reshaping the manner in which the EIC does business, so click on that Wiki link and read up on the battle.

What is important to know is that in 1756, the Black Hole of Calcutta happens. Some of y’all may think this is just a weird expression your mom always used to describe the states of her purse, but it was an actual event, and a horrific one. Siraj ud-Daula, who legit was not a fan of the British, captured a bunch of British soldiers (these were both actual British and Anglo-Indian soldiers) and imprisoned them in the dungeon at Ft. William.

The long and short of this is due to overcrowding and excessive heat, and probably lack of sufficient oxygen, most of the prisoners died in this roughly 22'x15’x12’ cell. There were 23 survivors out of 146 total. There is a lot of scholarly debate about how many victims there were, as well as other details, but the long and short is that this made a lasting and really bad difference in how the British handled their colonial subjects in India. It became a lot more brutal. Ft. William, and by extension, the dungeon referred to as “the Hole,” were demolished in 1818.

Here is a quote, grabbed off Wikipedia but from John Zephaniah Holwell narrative, A genuine narrative of the deplorable deaths of the English gentlemen, and others, who were suffocated in the Black-Hole in Fort-William, at Calcutta, in the Kingdom of Bengal, in the night succeeding the 20th day of June, 1756, in a letter to a friend. You can read the entire letter in that really long title’s hyperlink. Titles were just written like that back then.

The dungeon was a strongly barred room, and was not intended for the confinement of more than two or three men at a time. There were only two windows, and a projecting veranda outside, and thick iron bars within impeded the ventilation, while fires, raging in different parts of the fort, suggested an atmosphere of further oppressiveness. The prisoners were packed so tightly that the door was difficult to close.

One of the soldiers stationed in the veranda was offered 1,000 rupees to have them removed to a larger room. He went away, but returned saying it was impossible. The bribe was then doubled, and he made a second attempt with a like result; the nawab was asleep, and no one dared wake him.

By nine o'clock several had died, and many more were delirious. A frantic cry for water now became general, and one of the guards, more compassionate than his fellows, caused some [water] to be brought to the bars, where Mr. Holwell and two or three others received it in their hats, and passed it on to the men behind. In their impatience to secure it nearly all was spilt, and the little they drank seemed only to increase their thirst. Self-control was soon lost; those in remote parts of the room struggled to reach the window, and a fearful tumult ensued, in which the weakest were trampled or pressed to death. They raved, fought, prayed, blasphemed, and many then fell exhausted on the floor, where suffocation put an end to their torments.

About 11 o'clock the prisoners began to drop off, fast. At length, at six in the morning, Siraj-ud-Daulah awoke, and ordered the door to be opened. Of the 146 only 23, including Mr. Holwell [from whose narrative, published in the Annual Register & The Gentleman's Magazine for 1758, this account is partly derived], remained alive, and they were either stupefied or raving. Fresh air soon revived them, and the commander was then taken before the nawab, who expressed no regret for what had occurred, and gave no other sign of sympathy than ordering the Englishman a chair and a glass of water. Notwithstanding this indifference, Mr. Holwell and some others acquit him of any intention of causing the catastrophe, and ascribe it to the malice of certain inferior officers, but many think this opinion unfounded.

So what basically happens is they pack too many people in this dungeon, and those people freak out because of overcrowding and mob one of the windows, many of them dying in that process. To be sure, lots of these men would have died no matter what, but if they had somehow been able to stave off the panic, it would have been far fewer lost. The import of this event in terms of how the British decide to rule India (and a bunch of other places) cannot be overstated here. Check out the video below, if you’re interested in this event.

We’re going to hop across the pond now, to colonial America. By now, you can see that England has spent an extraordinary amount of money it didn’t have to engage in colonial pursuits across the globe. She really did need to recoup her losses somehow, and largely this gets done with taxes.

Americans mostly think about colonial taxes with regard to the Tea Act (1773), but in reality there were a bunch of these acts, beginning with the Molasses Act of 1733. They’d been hemorrhaging cash for centuries at this point in furtherance of spice acquisition and dominance of these types of trade, and colonies in regions where there was an abundance of material wealth like those in the Caribbean and North America were prime properties to tax for this.

Protest has always been of foundational import in this nation, and these American colonial subjects were all about it even as early as the Molasses Act. By the time we go through taxation Act after taxation Act and get to the Tea Act, there’s such a build up of indignities, it really does break the colonists and spur them to action. Between these two acts, there were insane amounts of protests, leading the Crown to repeal or otherwise modify the vast majority of these taxation acts. It also led to a rich smuggling industry, because Americans began to boycott British luxury objects. They weren’t going to go without them, but they were going to do their best to keep those monies out of the hands of their evil overlords.

William Pitt writes, after the Stamp Act:

My materials were good. I was at pains to collect, to digest, to consider them; and I will be bold to affirm, that the profits to Great Britain from the trade of the colonies, through all its branches, is two millions a year. This is the fund that carried you triumphantly through the last war. The estates that were rented at two thousand pounds a year, threescore years ago, are at three thousand at present. Those estates sold then from fifteen to eighteen years purchase; the same may now be sold for thirty. You owe this to America. This is the price America pays you for her protection. And shall a miserable financier come with a boast, that he can bring “a pepper-corn” into the exchequer by the loss of millions to the nation? I dare not say how much higher these profits may be augmented.

It’s worth noting here that a large portion of the offense related to these extra taxes is embedded in the reality that by “the end of the colonial period the value of products imported from the British Isles was between two and four million pounds sterling per year.” Slapping a lot of taxes on such an extraordinary amount of money already being funneled back to England legitimately was just too much to bear.

Although I should have mentioned it earlier, the first tax levied against Massachusetts (a name whose spelling I can never remember and always have to look up, but which is the first colony this happened to) was in 1638, did include pepper, and was worth a whopping one-sixth of the purchase price of such. This is a 16.7% tax. In contrast, the highest average state sales tax in America is in Alabama, at 5.22%. Here in Houston (Sabrina is the one in California, for those of you who don’t know, though I am from California), state and local sales taxes combine to 8.25%, which is less than half the first tax levied against colonial Americans.

So why are we even talking about this stuff everyone already knows? Because pepper is relevant here. Pepper, and also vinegar, were not included in colonial rations. Accordingly, pepper was super expensive and its use in the colonial period is largely relegated to persons of means, though this becomes less so over time. The vast majority of colonial foods really are very simple, plain fare.

Depending on where you were, anyway. Elihu Yale, who later uses his spice monies to found Yale University, started a spice business in 1672. He had previously worked for the East India Company, and used his contacts there to become THE spice guy in America. Later, the seat of spice power in America sits in Salem. Yale was also really active in the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, which we’ll discuss in more detail in a bit.

Yale.

Eventually, America had enough of all the taxes they had no say in, and they freak out and spill all that tea! You guys know the story. Well, y’all know part of the story. The manner in which the Continental Army, funded and supported otherwise by the French, in highly oversimplified form (but still how I remember it being taught in grammar school), trounced all over the British troops and WOO HOO! America is born. This successful revolt spurs others throughout England’s colonial holdings.

The Revolution is, from an imports and culinary standpoint, not awesome for the colonists. Because they had reduced access to things that didn’t grow here, since France (despite its deep love of pepper by this time) didn’t have as much power in the spice game as Britain did. They’d taken their licks and focused on other forms of colonial wealth acquisition.

It’s also worth noting here that often, Continental soldiers were not receiving the rations they were meant to. Part of this is because the Continental Congress was just flat broke for a lot of this, and so this was a war of spirit that somehow was won despite the hunger in soldier’s bellies.

This part of American history has been so heavily romanticized into national mythologies, that most people really don’t know what a problem food for the soldiers was. Let’s watch a video on that. Most of what Mr. Townsend will talk about in this is related to salt, which is the only spice that has a history as complicated as that of pepper.

This video gives you a bit of a clearer picture about the challenges inherent in feeding the Continental Army. I’m going to link one more video, because it’s my favorite YouTube channel and also because it does paint a clearer picture of what all these men were surviving on. If this is a topic of interest, Townsend and Son does an amazing job of bringing this type of history to life.

Poor Ross came into my room while I was reviewing that last video to ensure it was the one I was thinking of. He was sad the music had ended, and then he remarked that it’s a wonder that there weren’t more reports of cannibalism than are already speculated about, given the woeful state of rations for soldiers. I concur, as famine was extremely common for these guys.. That link above, by the way, mentions Washington’s wooden teeth. Worth noting here that the wooden teeth are another national myth.

These were teeth removed from the mouths of slaves. These slaves were alive during the extraction processed. They were also paid by Washington for their teeth, though I think it’s unreasonable to argue than any enslaved person is actually consenting to this type of procedure even if they are good with profiting from it happening to them.

“According to George Washington’s ledger, on May 8, 1784, he paid 6 pounds 2 shillings to ‘Negros for 9 Teeth on Acct of Dr Lemoin.’” This is listed in the 6th “By” from the top.

Back to England and the East Indies

Before we discuss how America gets in the pepper game in a real way, it’s worth noting that by 1716, the East India Company “consistently failed to fulfil their quota for the shipment of 200 tonnes of pepper a year.” This continues to decline as the EIC keeps ramping up its dominance in textiles. Fiscal mismanagement by the “men on the ground” for the EIC was so significant that “[n]onetheless, shipments continued to decline throughout the early eighteenth century, forcing the directors to conclude that ‘We have not been so well dealt with as We expected in gratitude as well as Duty & Fidelity’” (Ibid 94). These guys were extraordinarily brutal to the indigenous populations supplying the pepper, as was the norm, but to such a degree that it reduced pepper production in sum.

Sumatra becomes incredibly important for making up the pepper differences happening on the mainland, and this also becomes particularly important in the late 18th-century, when we get back to America. Which we’re doing now, because we need to talk about the Triangular Trade next.

Triangular Trade

By the mid-18th, pepper plants had been brought to French Guiana, and from there it spreads all over the tropical Americas.

Triangular Trade is a term meant to describe trade lines between Britain, Africa, and America. All of this rested on the backs of slaves, without whom none of the related industries would have been able to flourish. The Trans-Atlantic slave trade is most of what people are focusing on when they talk about Triangular Trade, but pepper mattered here too.

How this functioned was that English merchants, sailors, and so forth wandered on down to Africa, bringing finished products to trade for gold, pepper (and other spices), and slaves.

Actually? I’m going to veer off here because I spent a number of years studying and teaching slavery studies, and I’ve found that there tend to be a lot of misconceptions and myths that are believed by people. We talked about pre-Triangle slavery in other posts, and how most of those slaves were white, but here most of the slaves are Africans spanning multiple tribal boundaries. African slaves owned by Africans in the pre-Triangle days were not used or treated in the same ways that African slaves owned by Europeans/Americans were.

Depending on the tribe that owned the given slave(s), slaves may have a place at the family table, or they may be isolated and used for work, or lots of combinations in between. They were not, as per European slaving practices, separated from other slaves who spoke the same language, and in a lot of instances, they were treated with more humanity than we see in the Triangle and post-Triangle days.

In the later days, this changes, and you see widespread kidnappings of members of this tribe by members of that tribe, who were then sold to Europeans for other goods such as firearms, precious metals, and textiles. Lest you believe this was relegated to Americans and Brits, not so. Europe on the whole was generally all about it, too.

This represents the Haitian Revolution, or Haitian Slave Revolution, which was conducted against the French from 1791-1804. They won, paving the way for other slave revolts. It wasn’t until 1848 that all French-owned slaves were emancipated.

Back to the ranch, pepper was an important facet of what was going on in the Triangular Trade. Once trade was completed in Africa, slaves were taken from Africa, through the Middle Passage, and to America. Those were then traded for locally produced goods, such as sugar, maize, tobacco, rice, chiles, timber, and all sorts of other sundies. Those American goods returned to England, where they were used both to sell locally and throughout Europe, and to process into new goods that could then be sold back to the colonies. It’s a genius racket, really, because you make oodles of money on all three points of the process. This is especially true because of the Navigation Acts, which mandated that only English ships were used for each leg of the journey. This keeps literally every penny possible in the Crown’s hands and then improves upon it with all the taxes.

As a result of this practice and its resultant African Maafa, all of the African peoples were most harmed by this trading scheme. Be aware that the following video, while devoid of graphic images, is clear about the atrocity in its verbiage. Some of you may wish to skip this video.

This lady does an amazing job explaining how the Triangular Trade set up worked, and why it worked so well. She skips entirely over pepper, because once there’s a push to colonize the Americas, it’s quickly known that pepper isn’t anywhere to be found on this side of the Atlantic unless you plant it yourself. If slavery is a topic of interest for you, it’s a great primer.

The Revolution happens, slavery is still happening on a massive scale, and now we need a new way to get into the pepper game from the Americas. Enter Jonathan Carnes.

Carnes was a roguish sort of fellow, a former privateer (pirate), who corners the pepper market in America. In 1794, he slunk back to Salem, empty-handed after losing his ship and cargo in an exploratory pepper adventure. He had sailed a direct route and learned, however, the extremely valuable secret that pepper was growing in West Sumatra! Then he sailed back.

Upon his return, he paid $8000 (6 pence per pound of pepper) in customs on 140,000 pounds of peppercorns obtained through trade directly with indigenous Sumatrans. He earned a 700% profit from his venture. This transforms Carnes into the king of pepper in America, in effect, for a little while at least. After a few journeys there, he found that other Americans had figured out the secret and were taking their own slices of the pie.

All of this shoots Salem, MA into first place in pepper, and it maintains its supremacy over the global pepper market until 1840. At one point, pepper in Salem paid for a whopping 5% of America’s total national expenses. What ultimately boots Salem out of first place is piracy. It’s always piracy with pepper, isn’t it?

By all accounts other than those of his wife, he was a truly evil man, if you believe in that concept. This, however, made him uniquely well-suited to the kinds of work necessary to effectively take over one of the oldest global trades within the span of about 5 years.

This is Carnes.

Wrapping Up

Throughout this series, I’ve been telling y’all about 5% of the data I have on pepper history. There’s really so much information that you’re getting only a tiny percentage of what I’ve learnt. In this post, it’s 2% due to all the craziness going on. We’re going to zip through the last nearly 2 centuries of this, because it’s fairly straight forward. At long last, something is straight forward!

All this Salem business feels pretty nope to Britain, and she does wrest control of spices back from the States. This kind of goes back and forth for a little while, until we eventually get to modernity. What is most important to know about England in this whole deal is that she is single-handedly responsible for the ubiquity and ease of acquisition not only of peppercorns, but also most spices in sum. If you ask me to teach you about cloves, for example, I’m just going to tell you to read the pepper series again. They’re the same story, where it’s mainly the minor details that differentiate their stories.

Although I can’t claim that this is the most contemporary source possible, it gives a good visual representation of how pepper fares when contrasted to other spices. It’s impressive.

Today, Americans are the second largest importers of pepper, requiring an incredible 650 million dollars’ worth of pepper each year! Tunisians are the top pepper consumers, if you wondered. Pepper also comprises a full 20-25% of the annual spice trade globally (sources vary). We toss those packets, but we sure do buy an awful lot of them so we can!

The graph for American imports graph paints a different picture, where pepper is substantially more yes to us than the other spices in the spice set.

As an aside, the EPA says you can use white peppercorns in place of mothballs. I did not know that, and I thought y’all might like to!

40% of all pepper today is grown in and exported from Vietnam, not India or Sumatra. Indonesians now produce 15% of global pepper, with India and Brazil contributing another 10% each. Those are now the major players in pepper farming, though pepper today is traded on the futures market.

The last thing I have for you guys today, other than gratitude for your patience in taking this very long journey with me, is a song that Ross believes y’all should have stuck in your heads too. He mainly expressed his own need for some levity after all the heaviness of pepper history, and thought y’all might appreciate it as well.

Next week, we’ll be taking a very short journey into why you guys shouldn’t worry about kombucha SCOBYs!