Pepper: An Origin Story, Chapter 2

Sonja Punz/Getty

Last week, we looked at the first few thousand years of pepper history. Today will be the much shorter High and Late Middle Ages (1000-1485)! Not shorter writing; shorter time frame. Probably longer writing.

I won’t be thorough about the end of this period in this post, because I see a lot of value in taking a step back and examining more closely how we got from Italian control of the spice trade to the onset of the Age of Discovery/Age of Exploration, to the institution of the House of Tudor (1485), and ultimately, to Elizabeth giving over control of huge portions of Asia to the East India Trading Company (EITC, which I also will refer to as EIC). Lot of “to” going on there. So we’re doing that next week after we get through the middle ages today, properly but without too many spoilers on how intense and crazy things are about to get in global history. All because of pepper.

This period, in the next post, of colonial expansion and corporate charters is a weird and complicated one, and I don’t think it should be separated from what happened with the EIC. Although we’re going to officially conclude our medievalism business right before the father of Henry VIII (Henry VII), there will be way more about what happens in the 15th-century in Part 3 than in here. I’m specifying Henry VIII instead of his dad, the one who actually started the Tudor line, because he’s the most famous/infamous Tudor due to bein’ all choppy-choppy with the wives’ heads. That allows those of you who don’t know tons about this period to still be familiar with roughly when we’re talking about.

This is the Henry VIII y’all probably don’t recognize. This is before he had gone mad, presumably from syphilis or the treatment they used at that time: mercury. Back then, you took mercury for 6 weeks to cure this disease, and we all know why that’s bad.

Henry VIII, oil on panel by an unknown artist, c. 1520; in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

This is the Henry you probably do recognize; the portrait made 15 years before his death. Ross calls him “Lord Chungus.” We are ending today’s journey before this guy enters the scene.

Portrait of Henry VIII, c.1532, formerly in the collection of Warwick Castle.

The 11th

Now that everyone understands where we’re ending with some known references rather than 7th-grade history class dates, let us begin!

By 1000 CE, we’re still looking at pepper in most places as a luxury item. Hardcore luxury item. It’s all over Europe; also in Asia in the same smaller, extremely expensive quantities as in Europe wherever in Asia it doesn’t grow. This includes China. Pepper doesn’t get really popular in China, however, until around the early 13th-century. By the 14th-century, it’s wicked popular with Chinese elites.

This is why Marco Polo is so relevant; it wasn’t just how much trade he engaged in as a member of a powerful Venetian merchant family and his appointment as Kublai Khan’s foreign emissary - it’s the fact that he wrote it all down. So y’all know, if you don’t know much about Polo but did start watching that show I recommended: leaving Marco with the Khan is really dramatized in the show, and it likely didn’t go down exactly like that.

I’m gonna leave off of this for now and toggle back and forth between different regions and times as needed.

By the 11th-century, pepper is important enough that you can pay your taxes with it. Not like, normal people like us, but people with a lot of money. Remember that at this point, most spice trade (primarily pepper still) is happening along the silk road (also called spice road sometimes) and is incredibly expensive by the time it gets past Venetian, Pisan, and Genoan merchants into the heart of western Europe. This Silk Road spans over 4000 miles, for reference. No trains, planes, or automobiles. The Italians were so good at controlling the distribution and therefore prices of pepper, they could charge whatever they wanted (i.e., price gouging). In Dutch, there is still the word peperduur, which means “pepper expensive” because of how prohibitively costly this humble drupe once was. If something is peperduur, we probably can’t afford it.

In 1066, William the Bastard wins at Hastings and bam! Saxon nobility toppled. They probably didn’t have a lot of pepper anymore. But their new Norman rulers definitely did. It really doesn’t take an eternity for Anglo-Normal society to be deeply enmeshed in the politics of pepper. When the First Crusades hit, England got involved, albeit not super deeply due to William II not having been in charge particularly long (8 years). He also hadn’t yet really had the time to set England up to be a major global power at this point in Anglo-Norman history.

This map is from circa 1090, which is right before the First Crusades. It’s very easy to see from the lines on the map how pepper was part of these raids on the Middle East. You can think of this as very early exploitation colonial attempts from Europeans against the East, because they weren’t super good at it yet. Practice, sadly, did ultimately make perfect, as we’ll see later in the series.

The First Crusade

What’s up with pepper and the Crusades? We all know that that was about religion, right? Right?!

Nah, not really. Religion frequently gets used as an excuse for war. Although it is definitely true that Christians from this era were rather… well, gung ho about spreading the Word, “excuse for war” is generally still what we’re looking at. It should be noted, also, that with most of the Crusades, non-European sources from the period generally don’t list these wars as nearly so “omg it was all that was happening!” as European ones do. If you’re into this period, I really recommend looking into non-Christian writings on these events. Fascinating stuff, y’all.

It is true that religious intolerance had impressively increased during this time in Europe, so we’re also not going to pretend that the religion excuse was exclusively window dressing. From 1096-97 (when this Crusade was getting going), there were brutal murders of Jews who’d been forced into pogroms, and lots of them, as well as massive amounts of deaths for “out” pagans, those perceived as heretics, schismatics, and others. This was most prolific in the northern part of France and the Rhineland, and really was kind of like a low-tech version of the Holocaust. This type of intolerance also gets us all set up for the Inquisition, which I think most of y’all know at least loose details about.

Although trade between the known parts of the world was already on the increase,

Trade between East and West greatly increased. More exotic goods entered Europe than ever before, such as spices (especially pepper and cinnamon), sugar, dates, pistachio nuts, watermelons, and lemons. Cotton cloth, Persian carpets, and eastern clothing came, too. The Italian states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa grew rich through their control of the Middle East and Byzantine trade routes, which was in addition to the money they raked in from transporting crusader armies and their supplies.

Pepper here is again at the forefront. Lots of other important goods were being sold to western Europeans, but pepper is still the most valuable spice. Actually? Within this context Europeans means western Europeans; I’ll specify if we head east. We don’t see any significant reduction in its cost for a while, because Europeans hadn’t managed to full-scale colonize the world yet. That particular ship sailed from Portugal to the India, but not for a few hundred years still.

So quite literally, those packets we toss were once the stuff wars were fought over. Big ones. Western Europe really does ramp it up in later Crusades, but trade is how they got into that game. The main spices they were seeking were: pepper, cinnamon, ginger, galangal, and clove. Cubeb peppers also enter at the end of this century, presumably because they learnt about them while Crusading.

I’m assuming this piece is from the 13th- or 14th-century, but am not positive. Either way, it represents the Council of Clermont: Pope Urban II presiding over the Council of Clermont, 1095.

The 12th

One thing we need to understand about the period is what’s involved in this process of bringing spices from one continent to another. We’re looking at an extraordinary amount of danger, that’s what. You have to travel while carrying large sums of currency over thousands of miles of distance. There are no debit cards. Pirates are a thing. A big thing, really, because not only do they take your stuff if they getcha, they also sell you into slavery.

Slavery was ubiquitous during this time. This had nothing to do with ethnicity like it does when the Trans-Atlantic slave trade begins, not only because race hadn’t been invented yet, but because slavery largely happened to people as a biproduct of bad luck, and a crime of opportunity on the part of whomever sold you. This is, of course, a vast oversimplification, without consideration for the humanity portion.

But, how this goes is that pirates or other brigands sometimes are more powerful than you while you’re traveling, and they take you and your stuff. People are worth a lot, so you get sold on the slave market. Or maybe you aren’t traveling at all and simply had the misfortune of living in a village that was raided. People are worth a lot, so you get sold on the slave market. Etc.

This sometimes happened to merchants, too. Merchants needed a crazy amount of money to hire security to see them through to the port-of-choice, and often you needed to replace that security when they were killed off. Moreover, you are dealing with different languages and cultures that you may not have known anything about before you got there, and it’s not like you can quickly Google translate and research local customs on the fly.

You are also now traveling through a region that’s enmeshed in multiple political/military conflicts, so that ups the danger quotient by a lot. They also needed to be able to carry a lot of supplies just to make the journey, so you are really talking about what effectively are parades of wealth. Moving target is what we’re talking about, and a really blingy one.

There also was no insurance for these kinds of ventures, so if you got robbed in either leg of your journey, or you ship sank on the way back with a full load of pepper, or whatever else happened? If you survived the event, you also just lost a literal fortune. No insurance. This was truly a “with great risks come great rewards” situation, for the lucky, cunning, and skillful few.

This is meant to represent Wimund, who by all accounts I’ve seen was hated by everyone. He was a bishop and a pirate/warlord, and eventually another bishop had enough of him and smote him. He’s from the Second Crusade era. Anyway, this guy is also called the Scourge of Scotland, so that’s really how people felt about the matter.

Now you have a better understanding of the danger. It’s worth noting that there are spices today that are still dangerous for merchants. In the trade of a number of spices, buyers really do travel with armed guards.

Moving on.

During this century, you see a big push to open up trade lines… no, to take control of trade lines so as to make the whole process more profitable for European merchants. There’s a lot of monarchical money put toward this, in some cases, because controlling spice makes you über elite, yo. Even more so than owning and consuming them. Basically, however, you see some consolidation of power during this period.

In England, you also get the Crusader-King, Richard. What a tactical genius! Also a horrible king, no matter how beloved he may have been. They probably only loved him because he wasn’t really home much. Just an awful king. It is, however, from this era that the Legends of Robin Hood draw from. If you’re into Robin Hood, check this book out. You can buy a hard copy, but all the materials are available for free. Rochester is amazing like that. When I taught Robin Hood pieces, I had my kids use that site. I really liked to assign the earliest pieces, since you had RH killing innocent people, refusing to pay on bets he’s lost, beheadings, and basically all the things you don’t associate with that noble Disney Fox.

Also, if you are into Robin Hood, I strongly urge you to check out the academic writing of Drs. Lorraine Stock and Stephen Basdeo. One of the classes I took from Stock, whom I quoted in the cucumber article, was on Robin Hood, and I really got into Basdeo’s work during that time. He’s also an 18th-centuryist and Stock is a medievalist.

Lest you maintain the completely accurate belief that all this Robin Hood talk is a tangent entirely unrelated to pepper, watch this video! It’s from 1955; the pepper jazz starts at 12:52, but I really wouldn’t skip over the first half of the episode! I am sincerely disappointed that I wrote my mid-semester paper on salt in the 1938 Errol Flynn film instead of pepper in this.

One thing of note that doesn’t pop up in the episode below is that in 1180, The Guild of Pepperers became a thing. They change names a bunch of times later, but yes; they had a guild just for pepperers. The Guild had a lot to do with ensuring the purity of spices, setting prices, weights, and so forth. They were based in London.

The 13th and 14th

By the time we get to the 14th, you start to see more accessibility across class strata in Europe, with basically all but the poorest being able to afford at least some pepper. Prices are coming down a bit, though not quite like they will once the whole of Europe gets tired of paying Italians jacked up prices for The Precious. Then, of course, the hunt for alternate routes begin in the 15th-century, and we’ll largely leave that for next week’s post.

At this point, you’ve got widespread use of pepper in China amongst the elite. This actually happens in the 12th, but we’re toggling this down here because what happens here is way too important to embed in another set of thoughts. In some cases, pepper’s popularity displaces the native Sichuan pepper, a different plant entirely but wow a potent one!

Sichuan peppercorns. These are still totally used, primarily in China, but much of their use by elites during this time is displaced by peppercorns.

The Great Khan

What happens here is that the Mongolian Khans start making some real progress on taking over the whole of China. I think most Westerners think about Mongolian history in terms of the exceptional militaristic force shown in the West, but it’s happening in the East during this era, too.

By the 13th, pepper is big enough that you’ve got Italians running amok (not really) in the East, securing control over various portions of the pepper trade.

All y’all probably know who Ghengis Khan was by reputation alone, but he was also the grandfather of Kubai Khan, in whom we are most interested currently. Kublai Khan was the ruler of Mongolian Borjigid from 1260-1294. In 1270, he launched a successful colonial mission to China, so it is here that the Yuan dynasty (1270-1368) begins. He gives grandpa credit for that, though, as the founder of the dynasty. That just happens to not be true.

They get nearly a hundred years out of it before the Ming dynasty plops the Yuans right out of the seat of power in China. The Borjigid do continue to hold power in Mongolia until the onset of communist rule in the 20th.

But during that time they held China? Oh, during that time! Kublai Khan is battling internal conflict on a pretty massive scale, with various plots to take over being suppressed. These are happening in Mongolia, China, and Korea, which had also become a Mongolian territory. He increases circulation of paper money due to copper shortages, cements local control over various commodities industries, improves upon the bureaucratic structure, and creates a caste system. Straight up uncool caste system.

Kublai Khan also makes massive efforts to protect the Silk Road, thereby ensuring better and continuous profits from spice and others trade lines. He creates a welcoming center for merchants and those of high status to economically thrive, ensures a highly effective postal system, and, in effect, produces an incredibly cosmopolitan structure that elevates the entire region both economically and in terms of the high status conferred by other governments to them.

Taoists are heavily persecuted under his rule, but Confusianism and Buddhism flourish, and Christian missionaries are actively sought out. Like, he wrote a letter to the Pope (in Latin!) at the time asking for more to be sent on over. Okay, we all know that he had someone write that down for him, but it’s his words on the page so he gets credit. Even if he used a translator. I don’t know; I wasn’t there.

Arts flourish, ceramics trade, all sorts of things. Kublai Khan strongly supports the sciences, funneling money into developments in that arena. He also was really big on understanding the people you’re ruling, so he switched Mongolian names over to Han ones and also kept Han advisors so he could rule more in accordance with local traditions and norms.

Kublai Khan really is a beast on the administrative front, and this dramatically influences the safety and efficiency of the pepper trade. Note that Kublai Khan already controlled the local salt trade, so extra spices is win win for sure. All of this glowing praise aside, the strong militaristic nature of his rule rained brutality on those in the agricultural and craftsmanship sectors of the economy.

I personally don’t interpret these horrors as deliberately intentional, and especially given how critical those areas of an economy are, but rather as a terrible but natural byproduct of the specific ways in which Mongolian militaries functioned. This isn’t just Mongolian militaries, though; it’s really all colonial militaries. In some cases, you see concerted efforts toward upping brutality levels, but although I am not an expert in this period or place, I didn’t come across evidence of that here.

It occurs to me that I’m telling you guys stuff about a dynasty you may not be able to situate geographically. Here’s the Yuan empire’s map:

It’s really a ginormous swath of land space that, as you can see, extends into multiple contemporary national boundaries.

Due to the import of the Great Khan’s influence,

[C]aravans with Chinese silk and spices such as pepper, ginger, cinnamon, and nutmeg from the Spice Islands came to the West via the transcontinental trade routes. Eastern diets were thus introduced to Europeans. Indian muslins, cotton, pearls, and precious stones were sold in Europe, as were weapons, carpets, and leather goods from Iran. Gunpowder was also introduced to Europe from China. In the opposite direction, Europeans sent silver, fine cloth, horses, linen, and other goods to the near and far East. Increasing trade and commerce meant that the respective nations and societies increased their exposure to new goods and markets, thus increasing the GDP of each nation or society that was involved in the trade system. Μany of the cities participating in the 13th century world trade system grew rapidly in size.

Along with land trade routes, a Maritime Silk Road contributed to the flow of goods and establishment of a Pax Mongolica. This Maritime Silk Road started with short coastal routes in Southern China. As technology and navigation progressed, these routes developed into a high-seas route into the Indian Ocean. Eventually these routes further developed to encompass the Arabian Sea, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and the sea off East Africa.

Along with tangible goods[;] people, techniques, information, and ideas moved lucidly across the Eurasian landmass for the first time. For example, John of Montecorvino, archbishop of Peking, founded Roman Catholic missions in India and China and also translated the New Testament into the Mongolian language. Long-distance trade brought new methods of doing business from the Far East to Europe; bills of exchange, deposit banking, and insurance were introduced to Europe during the Pax Mongolica. Bills of exchange made it significantly easier to travel long distances because a traveler would not be burdened by the weight of metal coins.

Because there’s so much I’d like y’all to know about this that’s way outside the scope of pepper (even by my standards), I’m giving you this documentary in case you’d like to know more.

This is basically where Marco Polo comes in, because his ultimate fanboi leanings about Mongolian and Chinese cultures, the Khan, and so on gave us way more records than we otherwise would ever have had. Polo actually functions as the inspiration for Columbus and other Conquistadors to venture across the Atlantic seeking alternate routes to Asia.

Spain

Backing up a few centuries and wandering over to Spain, it’s important to note that in 711 CE, the Moors invade and take over a lot of Spain by around 718. The Moors (mostly Berbers but also some Arabs) were honestly not doing a great job over here. Come 755, Abd-er-Rahman enters the scene, and he transforms Spain into a cultural center, similarly to how this works over in the east with Kublai Khan. Not the same, of course, but it’s a big deal and they become a much wealthier society with, overall, a more egalitarian rule. A lot of Spain’s current cash cows, like saffron, become so during Abd-er-Rahman’s rule.

That said, there is still massive religious conflict, with both Muslims and Christians doubling down on the fanaticism and extremism scale. The word Matamoros, for reference, means “the Moor slayer.”

In 1010, the situation just explodes. It’s really bad. People are dying in mass numbers from the warring, reinforcements are being sent over from North Africa, and suddenly, the tolerance that governmentally did exist for Christians and Jews evaporates, leading to even more gruesome death. This goes back and forth, tolerance, no tolerance, over the centuries.

Stripping out basically all the history, what ultimately happens is that Ferdinand and Isabella gain control of Spain in the late 15th. This ushers in the era of the Conquistadors and the European race to control all other continents. Giving you another video for the history, because it feels not okay to leave so much out.

Although the periods of intolerance were really bad, what happens next is lunacy. The Moors did generally enjoy a good relationship with the Jews, and so Jews had an elevated status during most of this period.

Isabella was truly a devout Christian, so she makes it a point to resolve these inequities by killing off the people who had the monies (so people in spice), who were scientists, known Jews and Muslims, and who might have been lying about their conversions to Christianity. It’s a strange logical structure, but this need to root out false converts results in the murder of at least tens of thousands of people. Researchers can’t agree on this, but estimates range from 30,000 people to millions. Part of the issue in getting a more accurate count is that it wasn’t always church tribunals. Some of this stuff, and presumably quite a lot of it, was done vigilante-style.

As she hacks-and-slashes through her domestic enemies, she launches the set of ships designed to both convert indigenous peoples of other lands to Christianity and to rake in as much cash as possible through an alternate route to spices. To pepper. This is how Columbus got funded. Although he sets sail earlier, the Portuguese were the first ones to find a successful direct route from Europe to India. Vasco de Gama is that guy, and he made it in 1498. When asked why he was there, he said he was there for Christians and spices.

By the end of the 14th-century (we’re talking about the 15th in this section, but toggling back and forth), Rome was getting a bit tetchy about how invested Italian merchants were in non-Christian societies. Rome is not good with Middle Eastern involvement in the spice trade, and certainly not good with Italians being so big in the game. Not good at all. They actually decided to send some people on along to notify a large number of Venetians that they’d been excommunicated for their misdeeds!

Once de Gama succeeds in a direct route, it really does take the wind right out of Italian economic sails. It also lowers the price of pepper in Europe sometimes, because Venetians and other merchants swapped supremacy as they effectively played Risk with the global economy.

After bopping back to England really quickly, we’re going to close part 2.

Pepper was such a big deal in England that dock workers had their pockets sewn shut so they couldn’t steal any. People could also pay their rent in peppercorns. There were periods where pepper cost more than gold or silver, too.

England dramatically expands its holdings, conquering Wales and Scotland, and then when the Black Plague comes, it wipes out literally half of the people in what becomes the United Kingdom. Massive peasant revolts and exceptional literature follow, and ditto the War of the Roses. If you’re a Game of Thrones fan, that book and HBO series were inspired primarily by this period of English history. The War of the Roses ends as insipidly as the 8th season of GOT in 1485, leaving Henry VII as the winner and installing the House of Tudor as the monarchy for the next 118 years. You need to know that very incomplete, loose history because we can’t get to the East India Company otherwise. And that is what we shall do next week: the Age of Discovery/Exploration and hopefully the East India Company!

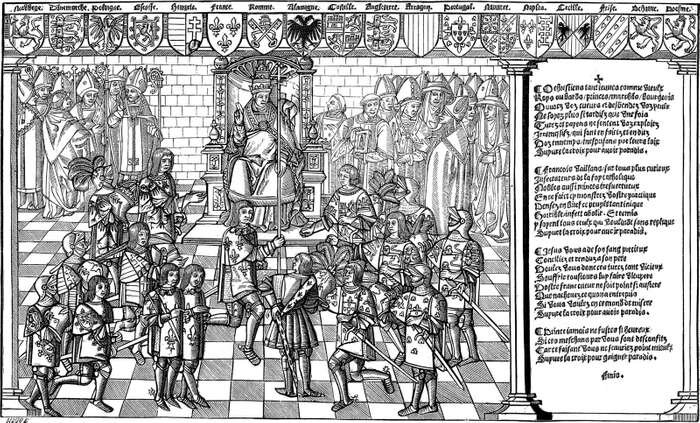

Gifts to kings = status for you. This is what Part 3 is going to be all about.

“A king is offered the fruits of a pepper harvest in this 15th-century illustration. (From the Livre des Merveilles du Monde, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, Bridgeman Images)”