Pepper: An Origin Story, Chapter 1

Tony Pham/Getty

I’m guessing that most of y’all toss those little packets of salt and pepper that come in takeout cutlery packages. Most people do. And that’s why we’re doing pepper today: my friend Jared and I are surprised every single time we see someone do this, because neither of us can wrap our heads around the idea of contemporary disposibility of pepper! Generally, you’ll see agreement amongst scholars that the history of the spice trade is, at its heart, the history of pepper.

So y’all know… actually, this won’t be a shock at all, because you already know I’m long-winded and that I already am bothered by the amount of info I leave out of each origin story. My original intention was to try to do this spice in one post, and then I realized that’s really not a great plan. Aside from the fact that I’m still dealing with the wrist issue and have also fallen ill over the last week, no one (including me) wants to have to read an article so long that it belongs in a journal. That’d be like trying to put all three honey posts in one. At best. So let’s all just strap in, because I think it’ll take 4 parts for me to get through the rich and storied history of black pepper!

I personally love pepper (Piper nigrum). Like, all of them. Black, green, pink (different plant, Schinus molle), long (also different plant, P. longum; this is my personal favorite), and white. They’re all full of yums. Ross and Child Tester are both hit or miss on pepper, seeming to care far more about the dose than I ever will. In case you’re not sure about the differences between them all, green pepper is unripe and dried peppercorn. Black is unripe, cooked and dried peppercorn. White is the fully ripe seed of the drupe.

Wait, what’s a drupe, you say? Glad you asked! A drupe is a fleshy, thin skinned fruit with a single seed. Plums, peaches, olives, etc. are all drupes. Stone fruits are what drupes are, in short. Blackberries and similar (but not mulberries) are aggregates of drupelets, which means a single flower with a long, multi-carpel pistil makes a whole cluster of tiny fruits!

Pepper leaves. Pepper has some of the more beautiful cordate (heart-shaped) leaves out there. Milena Troponova/Getty

Homeland

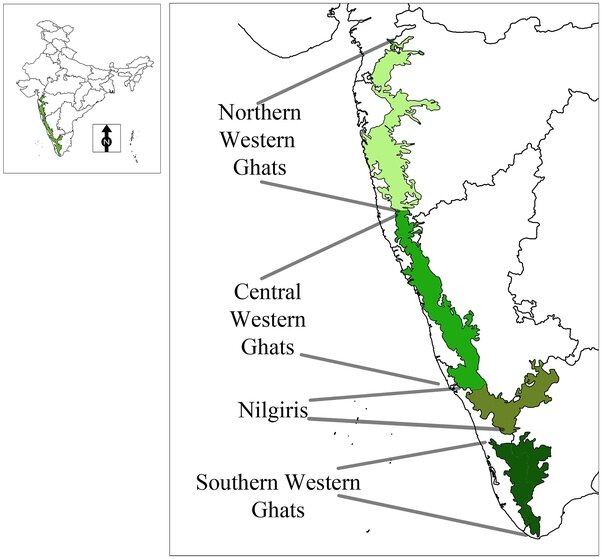

Pepper is originally from the Kerala region of India. As you’ve likely noticed by now, many, many things we eat come from India! The wild vine (pepper is a climbing vine, if you didn’t know) grows in the West Ghats mountain range (which is in Kerala and some other states). Map time!

Kerala is at the bottom left of India. The West Ghats range through multiple states in India

Western Ghats mountain range.

From here, peppercorns spread around, as foods do. Peppercorns are particularly important, though, because they become a mainstream form of currency in a number of regions the spice travelled to. There’s not much known about how it left Asia and moved into the Middle East and North Africa, but we know that it had done so by 1213 BCE. Black pepper was found in the tomb of Ramesses II, who died in that year. What we do know, however, is that Arabic traders did, by around 1000 BCE, control the larger portion of the spice trade and routes, so pepper’s entry into Egypt was probably a portion of the process of taking control of the spice trade. At this time, if you weren’t in a place where pepper can be grown, you were only using pepper if you were rich. Really rich. Like, emperor rich.

The Arabic spice monopoly is really similar to the Italian trade monopolies you see in the Mediterranean and west of such later on down the line, which is how we get to “meet” interesting historical characters like Marco Polo a couple of thousand years after Arabic traders had begun to secure control of the known global spice trade. I used to love that game as a kid, though it never really made sense to me, but I like the Netflix representation of Polo better than the swimming game.

I’m veering off track as usual, but here’s the official trailer, if you haven’t seen this exceptionally beautiful and cancelled-too-early show. Even if it weren’t such well-written and performed historical fiction, from the cinematography standpoint alone it’s worth watching. I was really sad that Netflix couldn’t continue to invest the massive amounts of money needed to keep this show going. They didn’t ever talk about pepper in the series, that I can recall, though.

By the time we get to the medieval period, which is when Marco Polo was, Italian and Arabic traders controlled the entirety of the trade of Asian and Middle Eastern goods in the Middle East and Europe. We’ll talk about Polo in Part 2 more, because although China has records of pepper as early as the 3rd-century CE, they don’t really get into the game, per se, until around Polo’s time.

Pepper quickly makes its way into Greece and Rome, and when Rome conquers Egypt in 30 BCE, it’s game on. The Romans send a massive fleet of ships along to get pepper! By bypassing the middle men, pepper just got a whole lot cheaper. Still expensive, though. According to Pliny, in 77 CE,

The root of this tree is not, as many persons have imagined, the same as the substance known as zimpiberi, or, as some call it, zingiberi, or ginger, although it is very like it in taste. For ginger, in fact, grows in Arabia and in Troglodytica, in various cultivated spots, being a small plant with a white root. This plant is apt to decay very speedily, although it is of intense pungency; the price at which it sells is six denarii per pound. Long pepper is very easily adulterated with Alexandrian mustard; its price is fifteen denarii per pound, while that of white pepper is seven, and of black, four. (Natural History 12.14)

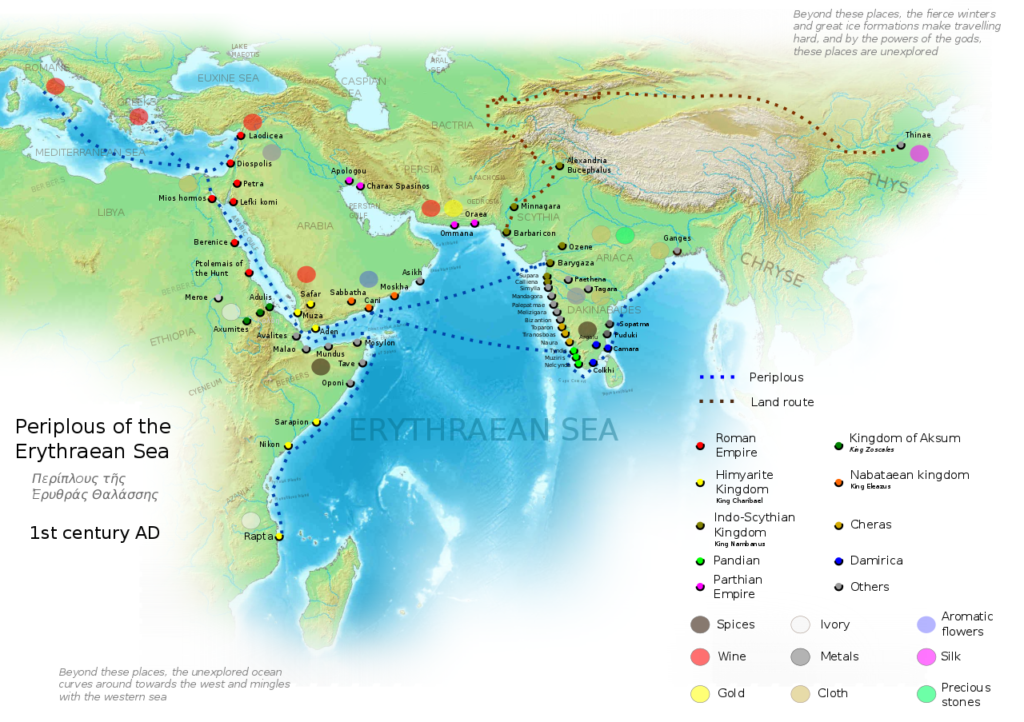

This is what the spice trade routes looked like around Pliny’s time. Remember that motorized ships, cars, and airplanes didn’t exist during this time, so you can see why it’s so expensive to move spices around. Also expensive because quite dangerous to be a spice trader! This is, with some spices, still true today about the danger part.

Pliny didn’t really get what all the fuss over pepper was about. Either way, once Rome was sending ships to get pepper, the cost did go down. For reference, a denarius has the bouillon equivalent to around $4. In purchasing power, though, it was worth around $58. Thus, the least expensive pepper you could get would cost you $232 for a single pound of peppercorns in 77 CE. If you’re working a minimum wage job, pepper is definitely not a thing you’re eating ever. For reference, the current market rate (futures) on black pepper is $4.36/kg, which is $1.98/lb. This is why people these days throw the packets away. I hadn’t done the math on this before writing this article, but my own question is now answered. We are talking about an extraordinary amount of work to earn that 2 bucks per pound, too:

Early Middle Ages

The early middle ages spans the 5th or 6th-century CE through the 10th (generally, 476-1000). We’re basically looking at this label as descriptive of most of the period during which the Anglo-Saxons were over in England. There’s a lot of crazy history going on during this time, but the history of primary importance for us is travel. Lots and lots of travel.

This massive start of migration is made possible by all the sackings and sieges of Rome, accelerating its final death knell during the 4th-centry. And pepper was part of that. Alaric got 3000 pounds of pepper out of the Romans as part of his ransom for releasing the city when he sacked Rome in 410. If we’re sticking with the $232/lb. figure, we are actually talking about a current value of $696,000 just in pepper to give Rome back. Plus all his other ransom demands. This ultimately sets up Rome for its more rapid demise in 476, establishes the Visigoth and other empires, the accelerates the Migration Period.

You have, at this point different groups of Europeans wandering all over the place, primarily for land, conquering of different peoples by different peoples, the births and deaths of bunches of empires, and pepper. Everyone, Pliny excepted, loves pepper. By the end of the 6th-century, we start seeing that things are now all about the spread of Christianity to indigenous European peoples, power consolidation, wealth accumulation and supremely beautiful artifacts. So many artifacts.

“John the Evangelist page from the Lindisfarne Gospels (c. 635 CE): As is common in early medieval art, the figures in this page appear flat and stylized. The bench on which John sits does not recede realistically into the space behind him. Modeling is kept to a minimum, and the clothing that John wears does not acknowledge the body beneath.” Y’all should check this whole page out, though, because there’s some astonishing art you’d probably like to see.

So where does pepper fit in with all this?

At this point in our history, Islamic control of the spice trade is complete within the middle section of the route, and Italians are raking it in on the western side of the puzzle.

This is how it was basically functioning during this period, and has a lot to do with the upcoming Crusades happening at all. Looking at the map, I’m sure you can see how.

Although a lot of people think pepper mattered a lot to Europeans because it masked the flavor of rotted meat, there’s zip for evidence on this. Really, given the extraordinary cost of pepper, you definitely could afford fresh meat if you could pepper it. But no, pepper was really just the bling of the European spice world. Got pepper? Must be monied, too.

Some people also view it as being used as a preservative, but pepper really does not contain enough piperine (the spicy component of pepper) to preserve foods on its own. It’s really just there to flavor it, irrespective of the medicinal benefits it truly does have. Medieval peoples really were quite a lot more sophisticated than we tend to give credit for, so these myths about the reasons they used pepper are part of a larger issue of primitivizing peoples who don’t enjoy the same technologies we do.

You know what they did use it for, though? Riddles! By the 7th-century, England had pepper in sufficient quantity for St. Aldhelm to write a riddle on it! His name, by the way, means “old helmet.” Northern Europeans at that time tended to have compound words for names.

This is my favorite Aldhelm, who is not acting douchey like it appears he is without the context for this scene. This is from the 4th series of The Last Kingdom, and I’m choosing to not offer context so you might feel like watching one of my favorite shows, too!

Anyway, our Aldhelm was from Wessex, and he’s especially interesting because he’s the first known Anglo-Saxon clergy to write in Latin verse. He was also really kind of a jerk to Britons about how their monks tonsured their hair. That is all important, but not as pertains to pepper. Aldhelm is relevant to pepper because of the following:

Modern English Text

I am black on the outside, clad in a wrinkled cover,

Yet within I bear a burning marrow.

I season delicacies, the banquets of kings,

and the luxuries of the table,

Both the sauces and the tenderized meats of the kitchen.

But you will find in me no quality of any worth,

Unless your bowels have been rattled by my gleaming marrow

Here’s a stained glass representation of St. Aldhelm.

St. Bede, one of the most important Anglo-Saxon authors, opted to give the other monks at Jarrow his small box of black pepper before his death. This probably was a gift to him from a higher status person.

Our last reference for today will be from Anthimus, a 5th-/6th-century Byzanthine physician who was sent… I guess like a gift, to the Frankish king Theuderic I. Anthimus was banished from his homeland at this time, so I imagine he didn’t mind so much. This is basically how recipes used to be written, so you’ll need to experiment if you want to try this out!

Meat Regarding meat, use cow's flesh steamed or cooked in the sodinga. [You can] Also [cook it] in gravy; boil it once to disinfect it, and so put in as much fresh water as is needed to cook and do not add [any more] water, and when the meat has been cooked, put the strongest vinegar in the vessel up to the middle of the pot, and put in heads of leek and a moderate amount of pennyroyal, parsley or fennel roots, and cook for an hour, and so add honey, as much as half as of the vinegar, or to have it as sweet as you want it, and so cook slowly on the fire stirring the pot frequently by hand, and well season the meat with its own juices. And so pound together fifty peppercorns, costus and spikenard each as much as half a solidus, and a tremissis' worth of clove. Pound all these things well together....

As for raw bacon which as I hear the Franks are wont to eat, I am surprised they find such a medicine sufficient, and that those who eat it so, raw, need no other medicine....

I really don’t know about y’all, but I’m gonna pass on eating raw bacon. By the end of the early medieval period, the main spices being imported were pepper, cinnamon, ginger, galangal, and clove. We start ramping up the luxury quotient next week, when we’ll look at the next 500 years of pepper history!